Table of Contents

Disclaimer:

The Volta flame experiment is an exciting demonstration of microbial activity and methane combustion, but it involves flammable gases and open flames, which can be hazardous. If you attempt this experiment, ensure proper safety precautions, conduct it in a well-ventilated outdoor area, and have fire suppression measures on hand. Always follow local regulations and, if possible, seek guidance from experienced individuals. Science should be thrilling, but safety always comes first!

Before It Was Written, It Was Lived.

If you want to learn something, just read the textbook—at least, that’s what we’re told. Textbooks are vast collections of what humanity has discovered, serving as references for lecturers and researchers (though for many students today, ChatGPT has taken that role). But knowledge doesn’t begin in books; it begins in experience.

Long before writing existed, our ancestors discovered fire. They watched the skies, traced the patterns of stars, and learned the rhythms of the land. Through generations of trial and observation, they cultivated crops, found healing in herbs, and passed down their wisdom, long before the first textbooks were written.

That same curiosity, the act of observing nature closely, has shaped modern science. Galileo, studying the heavens, saw Venus go through phases like the Moon, a quiet revelation that defied the prevailing belief of the Church that Earth was the center of everything. Gregor Mendel, in his monastery’s garden, noticed patterns in how pea plants inherited traits. He wasn’t studying genetics—the field of genetics didn’t exist yet—but his meticulous observations laid its foundation.

All knowledge, before it is recorded, is first an experience—an encounter with nature, a moment of discovery, the pulse of the unknown felt through careful and relentless observation.

We Used to Marvel at The World but Something Changed in Us.

A few years ago, I came across a video of the Volta flame experiment at Cedar Swamp as part of the Microbial Diversity tradition at the Marine Biology Laboratory, posted by George O’Toole .

A Microbial Diversity tradition - the Volta experiment in Cedar Swamp. Gotta love those methanogens!! #MicroDiv2019 pic.twitter.com/CZQpkjRl4N

— George O'Toole (he/him/his) (@GeiselBiofilm) July 10, 2019

The experimenter disturbed the pond sediment, capturing the escaping gases in an inverted funnel before setting them alight. A burst of flame whooshed out, fueled by methane released from beneath the water. Wow! I was amazed and immediately shared it with my close friends. Anytime I talked about microbes or methane, I would show that video.

“There are methanogens down there.”

“Of course, methane burns.”

“That’s how a portable stove works.”

But the more I watched, the more the magic faded. It became just another fact, like taking Panadol for a headache without ever thinking about the science behind it. The sun rises and sets with perfect precision, never late, yet how often do we even notice? I was reminded of a speaker who once shared how her child was mesmerized by birds flying. She had told herself, “But of course, birds fly—that’s what they do”.

We rarely pause to marvel at the everyday wonders around us. Somewhere along the way, we lost that childlike wonder. But strangely, it never crossed my mind to try the experiment myself.

“Because why would I?”

“I already knew the outcome—methane is there, light it up, and fire whooshes out. Duh.”

“And besides, where would I even do it? What if I bought all the equipment (it was cheap, but still money) only for it to fail?”

“It’s fine, really. I’ve seen the videos. I already know what will happen.”

A Bit of Personal Background.

I am Zarul Hanifah, living in Shah Alam. I studied in Monash Uni Malaysia in 2014, and I dropped by the Genomic Facility there in the middle of 2016, and fell in love with the world of microbial genomics. I continued working there in 2019, through the COVID years and started PhD at the end of 2021. My work was about long reads shotgun metagenomics on a Malaysian Peat Soil microbiome. I was known as the bioinfo guy back when I was working, so I was fortunate to have the Malaysian Steve Irwin, Azam (my business partner too, the CFO) to guide me in the peat forest. And there are so many friends who volunteered for numerous trips to the forest, in the name of science. Thank you guys.

Arigatou gozaimasu bros.

So, this pursuit started in 2022. Methane is always the big thing in peat research. So, I was looking for the methanogens in my dataset. And in the back of my mind, I always think of the Volta flame experiment. So, three years passed, and nearing the end of my final presentation, I read about the fulfilling life of Sergei Winogradsky, the first Microbial Ecologist. He uncovered microbes that drive the nitrogen and sulfur cycles, fled the Russian Revolution, took a 15-year hiatus, then resumed his research at the Pasteur Institute—where he even had his own lab. A life of adventure and dedication, enviable to any scientist.

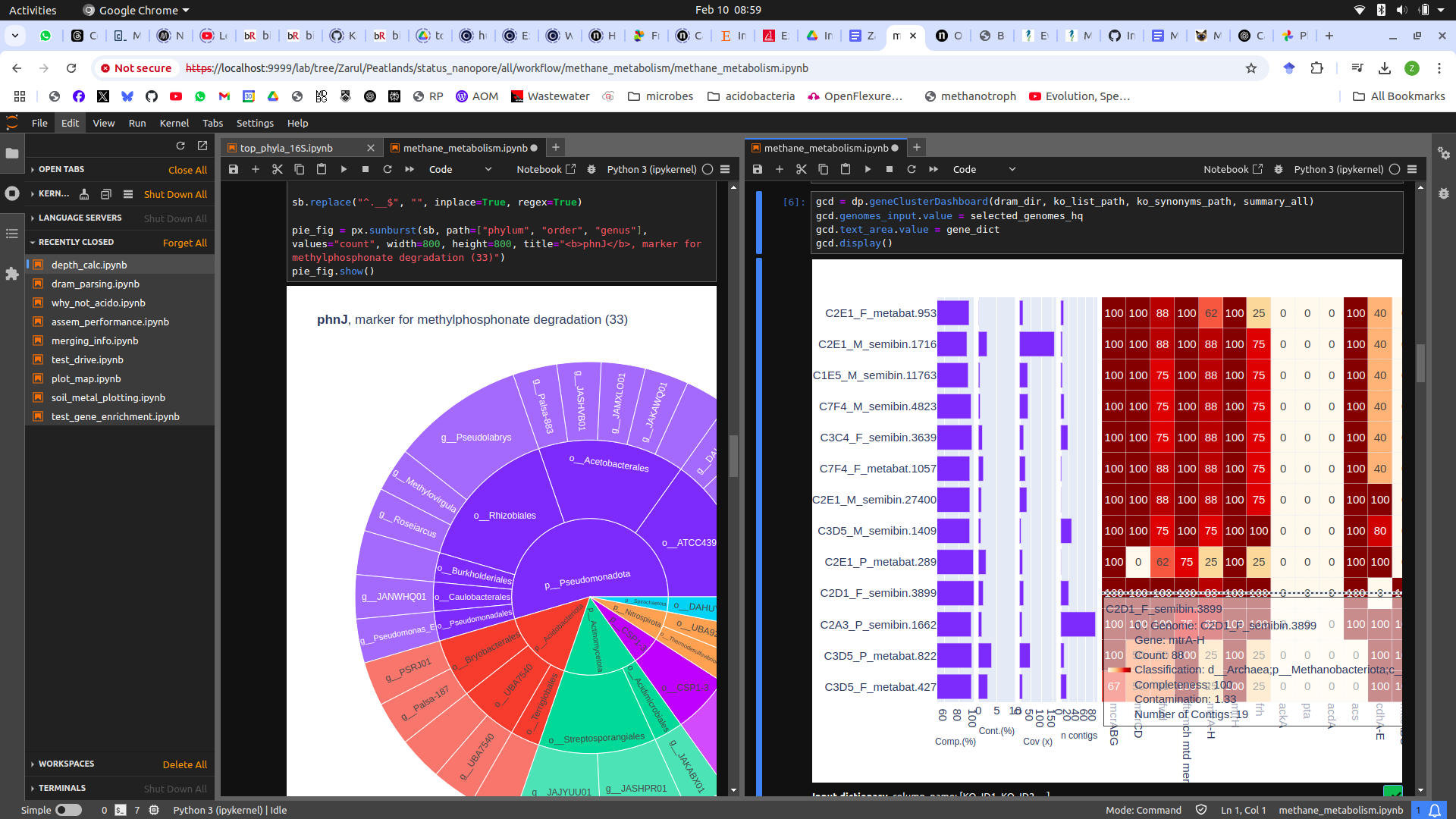

My screen few days before my milestone presentation. Bogged down behind the screen and eating unhealthily.

So after my final milestone presentation, we had one more trip as a grand finale to my PhD to finally do the Volta Flame experiment. Azam is necessary, the default driver. And this time, we were accompanied by a few young enthusiastic interns.

The Thrill of The Hunt

We left at 8 a.m., only to realize—half an hour into the drive—that we had forgotten the most important piece of equipment: the funnel. So, we turned back. This wasn’t the first time something like this happened, and Azam, as always, was incredibly patient.

With everything finally in order, we headed to the forest. The car ride was filled with endless conversation—we talked about everything, sometimes to the point where I was exhausted, but the flow never stopped. We were just happy to be in each other’s company.

At the site, we assembled the funnel with a tube. I had watched all the videos, but I hadn’t actually read a proper protocol on how to put everything together. We winged it. I had bought the biggest funnel I could find online, but the end was wider than the tube. To prevent leaks, we sealed the connections with balloons and cling wrap.

Assembling the funnel and the tube.

We got down into the water with the funnel, disturbed the sediment, ignited it—and nothing happened. Now I remembered why I had hesitated to try this myself. Maybe I should have read a protocol.

Maybe we picked the wrong spot. Maybe we didn’t collect enough gas. We kept trying, failing again and again—until finally, we got a BOOM.

It was exciting! But all we got was the sound—we couldn’t see any flames. I heard it, or at least I thought I did… I asked the others, and they all heard it too, so at least I wasn’t imagining things.

We decided to try a different site. This time, I adjusted the funnel setup, making sure there were no leaks. We tried again—another boom, then another—but still, no flame.

We tried a silly trick to collect the gas. This was probably how we looked like to the fishes underwater:

And it worked!!

@azamuddeennasir Kali ini kami di Fast Genomics Solutions ke kawasan paya gambut untuk melihat proses penghasilan methane daripada mikroorganisma khususnya "methanogenic Archaea". Kami telah menyediakan uji kaji mudah dimana kami menggunakan corong untuk mengumpul gas-gas yang terperangkap di dasar air. Seterusnya kami nyalakan api untuk melihat jika ada methane yang wujud. Disebabkan methane ini adalah bahan pembakar, corong itu akan mudah terbakar dan akan menghasilkan api yang besar. Penafian! Uji Kaji ini haruslah dibuat oleh pakar-pakar yang dilatih. Kami telah mengambil langkah-langkah berjaga apabila mengendalikan uji kaji ini. Alat-alat pembakar api sentiasa berada berdekatan. _____________________________ This time, we at Fast Genomics Solutions visited a peat swamp area to observe the process of methane production by microorganisms, particularly methanogenic Archaea. We conducted a simple experiment using a funnel to collect gases trapped at the waterbed. Next, we ignited the collected gas to check for the presence of methane. Since methane is a flammable substance, the funnel would catch fire easily, producing a large flame. **Disclaimer!** This experiment should only be conducted by trained professionals. We have taken necessary precautions while handling this experiment, with fire-extinguishing equipment always on hand. #biodiversity #education #hutantalk #conservation #archaea #methane #peatswamp #CapCut ♬ original sound - AnakUmiSukaHutan

And we shouted the same words the first discoverers of fire must have uttered:

WOOOOOOOO!

It was truly amazing. Wait… I had watched so many Volta experiment videos before. Wasn’t I supposed to know exactly what to expect? But seeing the flame firsthand—it was different.

After all the setbacks, we kept trying—tweaking one thing, adjusting another—and in the end, we were rewarded with the flame. Maybe this was what Sergei Winogradsky meant when, after a long day in the lab, returning home, he said to himself:

‘Then one day as I was following the Île canal on my way home after a tiring day of chemical work which also involved hydrogen sulfide and sulfur, it suddenly occurred to me that sulfur might be oxidized by Beggiatoa to sulfuric acid. I could at once appreciate all the significance and implications of my conjecture, having no doubts that it offered the solution to my problem… The work was humdrum, it dragged on and on sluggishly, and all of a sudden it developed into an interesting result and was finished. All the beating around suddenly made sense, and I matured in my own eyes…’

To compare ourselves with the First Microbial Ecologist who contributed immensely to the discoveries of sulfur and nitrogen cycle, that is a bit too much, but we will celebrate this success anyway.

Further Reflections

The team and the cameraman.

Knowledge isn’t just about knowing—it has to be experienced to truly understand its value. The WOO sound that erupted from seeing the first flame; it was the same thrill that must have driven scientists before us. Science is meant to be exciting, but too often, in formal education, it’s reduced to routine lectures in dark halls and short lab sessions shared with 40 other students, with barely enough resources to go around.

That’s why this experience felt so special. The excitement of discovery was contagious—Azam shared our experiment online (another one below), and many people on social media were just as awed as I was when I first saw the Volta experiment on video. We were especially grateful that we brought the interns along, hoping they would inherit the same passion for science. When we asked them how this compared to their university lab sessions, they said this had to be one of the best.

@azamuddeennasir Video ini ialah huraian berkenaan fenomena Methanogenesis. Methanogenesis atau proses penghasilan methane adalah proses khas daripada kumpulan Archaea. Tiada mikroorganisma lain yang boleh menghasilkan methane. Methane ini sebenarnya tidak mempunyai bau, bau busuk yang selalu dikaitkan ialah daripada bahan sulfur yang selalunya dihasilkan bersama. Ramai penonton dari video saya sebelum ingin tahu adakah ini fenomena yang dipanggil sebagai Sulur Bidar? Jawapannya betul! apabila proses pereputan berlaku, gas-gas yang terhasil secara semula jadi akan naik ke permukaan air. Tetapi kadangkala, gas itu akan terperangkap dan terbina sehinggalah ia naik ke permukaan sekaligus seperti ledakan gas. Gas yang naik ini membawa sekali bahan-bahan organik yang terperangkap di dasar yang membuatkan ia sering dikaitkan dengan perkara mistik. Penafian! Uji Kaji ini haruslah dibuat oleh pakar-pakar yang dilatih. Kami telah mengambil langkah-langkah berjaga apabila mengendalikan uji kaji ini. Alat-alat pemadam api sentiasa berada berdekatan. ______________________________ This video is an explanation about the phenomenon of Methanogenesis. Methanogenesis, or the process of methane production, is a specific process from the Archaea group. No other microorganisms can produce methane. Methane itself is actually odorless; the foul smell often associated with it comes from sulfur compounds that are usually produced alongside. Many viewers from my previous video wanted to know if this phenomenon is called Sulur Bidar. The answer is yes! When the decomposition process occurs, gases that are naturally produced rise to the water's surface. However, sometimes the gas can become trapped and build up until it rises to the surface in a burst, like a gas explosion. The gas that rises also carries organic materials trapped at the bottom, which is why it is often associated with mystical phenomena. Disclaimer! This experiment should only be conducted by trained professionals. We have taken necessary precautions while handling this experiment, with fire-extinguishing equipment always on hand. #peatswamp #methane #archaea #conservation #hutantalk #education #biodiversity ♬ original sound - AnakUmiSukaHutan

The Volta Flame experiment is such a simple but powerful demonstration of microbiology’s impact. It’s a reminder that we are living in a microbial world, even if we can’t see it. In retracing the steps of Alessandro Volta, I can’t help but wonder—how did he feel when he first saw the flames dance above the swamp gas? Did people think he was crazy for venturing into the marshes of Lago Maggiore to trap invisible gases? I would love to read his own words about this moment, but I haven’t been able to find them.

Maybe that’s part of the adventure—rediscovering the same wonders that once inspired the scientists before us. Hoping for more adventures to come!

References

- Axpo. The Twitching of Dead Frogs. Axpo, https://www.axpo.com/lu/en/about-us/magazine.detail.html/magazine/energy-market/the-twitching-of-dead-frogs.html.

- Martin Dworkin, David Gutnick, Sergei Winogradsky: a founder of modern microbiology and the first microbial ecologist, FEMS Microbiology Reviews, Volume 36, Issue 2, March 2012, Pages 364–379, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00299.x